Savage Carnival: Wild Man’s Dance

The “Wild Man” has popped up in stories across all kinds of cultures for centuries, acting as a reflection of society’s biggest fears, fantasies, and worries. This blog dives into how the “Wild Man” doesn’t’ just show us what’s going on in different cultures at specific times: the “Wild Man” also pushes boundaries and reinvents his meaning with each new era. This blog dives into the 1923 silent film accompaniment “The Savage Carnival: Wild Man’s Dance, composed by Erno Rapee and William Axt, which was used to depict scenes of so-called “cannibals,” often stereotypically associated with native islanders or African tribes. Through this lens, the blog examines how the music amplifies the “Wild Man” archetype and reveals early 20th-century Western fascinations - and misconceptions - about native cultures. Also, the word “savage” has taken on a strange new life, often used to describe someone who’s brutally honest, fearlessly confident, unapologetically authentic, masterfully skillful, or even witty. But while it might sound edgy or cool to some, this word carries a painful history. Until recently, a college performance group even used it in their name. For students of Native heritage, hearing these terms thrown around can feel like a slap in the face, reminding them of stereotypes and discrimination that society hasn’t fully moved past. When we casually use language that has marginalized entire groups, we risk alienating people and downplaying the real impact of these words. This idea connects to a broader conversation about how we construct cultural “monsters” - figures that embody society’s fears, anxieties, and prejudices. In his Monster Culture (Seven Theses), Jeffrey Jerome Cohen explores how monsters serve as powerful symbols, each reflecting the values, boundaries, and taboos of their time. By exploring the intersection of silent film music and monster theory, we gain a deeper understanding of how cultural anxieties and prejudices have been expressed and reinforced through both visual and auditory means. The study of these elements provides valuable insights into the complex ways in which society constructs and deals with the concept of the Other.

Monsters have always been part of human history, lurking at the edges of our imagination and reflecting our deepest fears. Picture those old medieval maps with creepy creatures sketched around the edges, as if to say, “Yep, this is where the weird stuff dwell.” Fast forward to today, and monsters are still everywhere - in our movies, our video games, even our stories. What’s fascinating is that every culture has its own set of monsters, and they’re never random. They embody what a society fears most, often representing the “othered” - anything or anyone perceived as strange, foreign, or threatening. Monsters, in a way are mirrors showing us our anxieties and boundaries.

Monsters in Music

Monsters and music have always had a close relationship. From the medieval era, where music could evoke a sense of evil, to witches in Elizabethan theatre singing eerie tunes, scary music has consistently set the stage for the unsettling and the unknown. Over time, this trend evolved to include music accompanying scenes that depict “othered” groups, often framing them with so-called “exotic” themes tied to “Indian, Chinese or African” cultures. And today? The tradition of tying scary music with monsters is alive and well in modern movie soundtracks and video game scores, where the right music can send shivers down our spines as we face monsters on screen. It’s always been about amplifying the drama and making those monstrous moments hit even harder. Rappe and Axt’s composition is a perfect example of this - it’s one of many pieces that uses music to enhance the sense of the monstrous.

If we want to really dig into this composition, we’ll view it through the lens of the monster trope. It opens up some fascinating questions: Why do monsters, like the “wild man” even exist? Why does society keep creating them in the first place? To unpack this, let’s continue on to Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s chapter Monster Culture (Seven Theses) - a framework that helps us understand why we’re so captivated by these larger-than-life, often terrifying figures.

Monster Theses

Cohen really nails it with his idea of a “new modus legendi: a method of reading cultures from the monsters they engender.” (Cohen 1996, 3). It’s such a compelling way to look at the stories we tell, the art we make, and what they reveal about the world we live in. Using this framework, I want to dive into Rappe and Axt’s composition Savage Carnival: Wild Man’s Dance. By examining this piece through Cohen’s lens, we can uncover some fascinating insights about the culture that brought it to life. Let’s explore what this “wild man” might say about the people who imagined him.

What are the 7 Theses?

Thesis I: The monster’s Body is a Cultural Body:

You know that idea of the “monster” Lurking in the shadows? It’s not just about fangs, claws, or creepy folklore. Monsters are born out of something deeper - at the intersection of a specific time, place, and cultural vibe. They’re like a snapshot of collective fears and anxieties. As Cohen puts it, “The monster is born only at this metaphoric crossroads, as an embodiment of a certain cultural moment.” (Cohen 1996, 4)

In the early 20th century, for example, the stereotype of “natives” as wild, primitive, or even monstruous was everywhere, especially in silent films. These depictions weren’t just random - they reflected a very real fear of the unknown: unfamiliar lands, different ways of life, and non-Western cultures. Indigenous peoples, the Near and Far East, Africa, South America, and even the Caribbean were all thought of as mysterious, dangerous “others.” It’s like the monster became a stand-in for this fear of anything that didn’t fit neatly into Western norms.

Thesis II: The Monster Always Escapes

You’ve probably noticed how monsters never really go away. Cohen makes a great point when he says, “No monster tastes of death but once.” (Cohen 1996, 5) They might seem defeated for a moment, but they always come back - sometimes in new forms but always tied to the fears and anxieties of their time. Cohen illustrates his point using the creature from the film Alien as an example. No matter how many times Ellen Ripley gets rid of the alien, its children keep coming back, each one just as determined to destroy her. (Cohen 1996, 4-5)

In our case, the Wild Man keeps popping up in myths, legends, and pop culture, adapting to fit the fears and fascinations of each era. The latest version? I guess it would be the Sasquatch, or Big Foot, (if indeed is real) is something primal, elusive, and just beyond our understanding. The monster embodies our ongoing dance with the unknown, and the untamed.

Thesis IV: The Monster at the Gates of Difference:

Ever notice how monsters have a way of turning the unfamiliar into something terrifying? Cohen explains how people transform the “othered” into a “monstrous aberration,” exaggerating cultural differences to the point of fear. This isn’t just about spooky stories - it’s a reflection of how people from different cultures have been dehumanized throughout history.

When it comes to the southern oceanic peoples, the way they were perceived from the very first encounters is pretty shocking. Captain Cook, for instance, didn’t hold back in documenting his experiences, (which weren’t published and available to the public until 1893, just 30 years before “Wild Man’s Dance” was composed, even though other accounts of the voyage were available since 1773) and his descriptions shaped how these communities were seen thereafter. One particularly infamous moment happened during his time in New Zealand in 1773. After battling relentless gales and losing contact with one of his ships, the Adventure, Cook and his crew anchored in Queen Charlotte’s Sound. It was here that they witnessed the Marois eating human flesh right in front of them. According to Cook, this wasn’t just an ordinary encounter - it was a way to silene skeptics back in England who doubted the stories of cannibalism. Let’s just say Cook was all about “proving” what he’d heard. But the story doesn’t end there. Things took a far darker turn when the Adventure eventually made it to Queen Chalotte’s Sound. A boat crew from the ship was attacked, overpowered, and reportedly eaten by the locals. None of the crew survived to tell the story, but the grim aftermath - cooked remains discovered as the search party arrived - cemented the narrative. This framing, while steeped in Cook’s perspective, highlights how early encounters with indigenous cultures were often sensationalized, “excluding them from personhood,” as Cohen puts it, and reducing their complexity to monstrous stereotypes. (Cohen 1996, 11)

Thesis V: The Monster Polices the Borders of the Possible:

Once a monster myth takes root, it becomes a powerful tool - especially for those in charge. Governments throughout history have used these stories to control both land and people. Imagine the pitch: “Be careful! There are reports of cannibals on that island.” Whether it was true or not didn’t matter. It was a convenient excuse to keep the land to themselves and exploit its resources while scaring people away from exploring or leaving. Monsters became a way to say, “Stay where it’s safe. Don’t venture out there.” This tactic isn’t new. Take for instance the old maps from medieval times. Ever notice those creepy monsters drawn at the edges? They weren’t just decorative - they were warnings. Often, these mythical creatures were placed in regions considered distant, rugged, or impossible to tame, like south of the northern African coast. Usually, depicted as very hot and barren (commonly referred to as Ethiopia back then). Similarly, remote islands in the middle of nowhere were perfect settings for monster legends. Their isolation and inaccessibility made them prime real estate for fearsome tales especially with the added reports of cannibals! It’s fascinating - and a little unsettling - how effectively the idea of “monsters out there” has been used to shape perception and keep people in their place. After all, why take the risk of exploring when the unknown is painted as terrifying?

Thesis VI: The Fear of the Monster is Really a Kind of Desire:

The idea of the monster doesn’t just apply to creepy creatures of far-off lands- it can also inspire creativity. For composers, the monster represents the “other,” something outside the norms and expectations. And because of that, it gives them permission to break free from traditional rules and possibly fulfill that hidden desire to “cut loose.” Instead of writing music that’s conventionally “pretty,” they can embrace the ugly, the chaotic, and unconventional. Take the savage Wild Man, for example - a figure who embodies defiance against societal norms and etiquette. A composition inspired by him doesn’t need to follow the usual structure of harmony. Instead, it can reflect his wild, unruly nature. Composers like Rappe and Axt did exactly this, as we’ll explore later. Their music is packed with dissonance and discord, perfectly mirroring the chaos and raw energy of the Wild Man and his untamed dance.

Thesis VII: The Monster Stands at the Threshold of Becoming:

In the end, the monster is really just a mirror - a reflection of us. It’s a projection of our biases, stereotypes, prejudices, and even bigotry. What we fear in the monster often says more about our own perspectives than about any real threat. Take the Wild Man’s Dance as an example. It’s not just music; it’s a snapshot of the composers’ prejudices toward aboriginal communities. Whether those fears and stereotypes came from their upbringings, their community, or their own personal beliefs, they’re clearly woven into the fabric of the piece. The “Wild Man” in their work isn’t just a character - it’s a manifestation of their anxieties, exaggerated and amplified through music. It’s fascinating - and unsettling - how art can serve as both a creative outlet and a window into cultural biases. In this case, the fear and misunderstanding of the “other” found a voice in the dissonance and chaos of the composition.

Historic Monsters in Music

Jacobus Leodinesis, Speculum musicæ, Liber septimus. (Source: Thesaurus Musicarum Latinarum (https://chmtl.indiana.edu/tml)

Monsters have always been a part of human culture, from myths and stories to visual art. But did you know that they’ve also made their mark on music? Even the world of musical notation has its own history with the monstrous! Let’s take a quick trip back to the early fourteenth century. Notation, believe it or not, were tied to creatures like the Chimera or the griffon. Luminita Florea’s wrote an article highlighting the representation of monsters in their article The Monstrous Musical Body: Mythology and Surgery in Late Medieval Music Theory found in the journal Philobiblon. In this article they focus on two instances where music notation and scale theory could be interpreted as representing monsters. The article mentions Jacques of Liege, a music theorist who was not a fan of the “modern” trends of his time. In a fiery critique, he lashed out at his contemporaries for introducing what he saw as musical monstrosities. These so-called “abnormal” note values, like the larga (or duplex longa), broke away from the traditional norms and, in Jacques’s view, disrupted the natural order of music. Jacques viewed the triplex longa as notation that feels utterly impractical in his time. Its ridiculously long value makes it seem more like an exercise in extravagance than something useful. Visually, it’s equally dramatic, with an oversized notehead accompanied by multiple “caude” (note stems) branching out in all directions (see the illustration above). These stems aren’t just for show - in the music theory of Jacque’s time they indicate whether the note divides into shorter values, called breves, in a perfect (divisible by 3) or imperfect way. (divisible by 2). But here’s where it gets interesting: Jacques described these new note shapes as actual monsters! He compared them to the Hydra or Lerna, the many-headed serpent of Greek mythology, or Cerberus, the infamous three-headed guard dog of the underworld. For Jacques of Liege, these notes weren’t just wrong - they were multi-limbed, grotesque creatures invading the purity of the musical landscape.

“Chimera” Scales

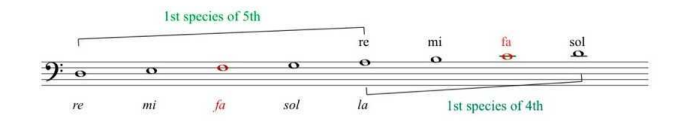

Have you ever thought about music modes as monsters? No? Well, Florea’s article also mentions Golino of Orvieto, a 15th century music theorist, did exactly that. He used the metaphor of mythical beasts to explain what happens when music doesn’t’ play by the rules. Think of it as a mashup of medieval theory and a touch of monster lore. Here’s the gist: Ugolino believed that each musical mode has its own natural balance - kind of like how every species has its distinct traits. For him, the “healthy” state of a mode is based on its intervals, particularly the perfect fifth and fourth.

Mode 1 outlined through its characteristic species of fifth and fourth

Mode 1, “Chimera”

But what happens when something disrupts this balance? According to Ugolino, the mode transforms into a “monster,” a deviant creation born from mismatched musical intervals. For instance, when a mode incorporates a B-flat where it wouldn’t typically belong, the resulting scale isn’t horrifyingly ugly or unbearable - Ugolino says it’s just… absurd. He compares this to mythical creatures like the Chimera, with its lion’s body, goat’s head, and serpent’s tail. In his words, this hybrid of mismatched elements is “contrary to natural reason.” In modern terms, it’s as if Ugolino is warning us about the risks of creating something so offbeat it defies all expectations. Ugolino’s metaphor is a quirky reminder of what happens when rules get bent just a little too far.

(For additional reading on monsters and medieval music see: The Monstrous Musical Body: Mythology and Surgery in Late Medieval Music Theory by Luminita FLOREA . Philobiblon – Vol. XVIII (2013) – No. 1 127 : Eastern Illinois University, Charleston)

The Early Modern Stage and Witches

If you’ve ever heard Come Away, Hecate! a haunting piece believed to be written by Robert Jonson for Thomas Middleton’s play The Witch (circa 1609), you might be struck by its eerie beauty. To modern ears, the piece might sound almost harmonious, but to audiences of the early 17th century, its subtle discordances would have been anything but ordinary. These musical choices weren’t just artistic flair - they were deliberate, designed to underscore the supernatural chaos of the scene. Take, for example, measures 20 to 30. Here, the music takes a turn that seems, on the surface, unsettling yet fascinating. The witch’s madness, a trait often linked in the era to dealings with the devil, is vividly expressed through haring shifts in the melody. One moment, the line is monotone, a flat and almost hypnotic drone. The next, it leaps dramatically by an octave, creating a stark contrast that mirrors the fractured mental state of the character. For contemporary audiences, this juxtaposition of monotony and wild leaps would have felt like an audible representation of disorder and madness - a stark reminder of the witch’s supposed pact with dark forces. And that’s not the only instance where the music subtly enhances the narrative. Further into the piece, rhythmic irregularities disrupt any sense of stability. Phrases end abruptly or linger longer than expected, creating an almost unsettling unpredictability. Even the interplay between vocal lines adds to the eerie atmosphere.

Come Away, Hecate! mm. 18-25.

Understanding these musical nuances gives us a richer appreciation for how composers like Jonson used their craft not only to entertain but to evoke and amplify the cultural fears of their time. The witches of Come Away Hecate! weren’t just characters - they were brought to life through discordant, unsettling sounds that tapped into the very real anxieties of 17th-century audiences about the supernatural.

troduction to Film music

Music written for silent films in the beginning of the 20th century was cleverly structured to be adaptable. Composers designed pieces with repeatable sections, allowing musicians to lengthen or shorten performances as needed. These compositions often leaned on semiotic techniques to reinforce narrative elements. For instance, M. L. Lake’s “Synchronizing Suite No. 1”featured thematic representations for characters like the hero, heroine, and villain. Subtle variations, such as shifting the hero’s theme to a minor key or adding dramatic tremolos to the villain’s motif, conveyed emotional shifts and heightened tension, enriching the storytelling.

However, this era of silent film music also reflected darker societal prejudices. Pieces like “Comic Darkey Scene” perpetuated racial stereotypes, revealing the troubling undercurrents of cultural narratives in the early 20th-century art. By examining these works critically, we gain insight into historical prejudices while appreciating the progress made in representation and inclusivity.

“Savage Carnival: A Wild Man’s Dance”

As discussed above, music that felt unsettling - anything disjunctive, or unnatural - was often labeled as “monstrous.” It’s fascinating (and a little troubling) to see how this idea played out in early film scores, particularly in the work of Erno Rapee and William Axt. Their composition fit this “monstrous” mold perfectly. Just like the historical examples above, we’ve seen they intentionally “deformed” certain musical elements to match the perceived deformities of the cannibal characters. In other words, they weren’t just scoring a scene - they were crafting soundscapes designed to evoke fear and disgust by manipulating musical norms. It’s a striking example of how music was used not just to tell a story but to reinforce deeply ingrained stereotypes. By making the music itself feel monstrous, Rapee and Axt mirrored and amplified the visual and narrative depiction of the “other.” To make the imagery as monstrous as possible. Rapee, along with fellow composer Axt, pulled out all the stops to achieve this effect. Let’s break down how they used music to instill fear, discomfort, and a sense of “otherness” in the listener.

Here’s how:

Dissonant sounds Create Unease

The music wasn’t meant to be pleasant. Repee and Axt were able to create pleasant music. There are many examples of compositions that can attest to their ability to create lovely comforting pieces of music to listen to. However, dissonance, in rhythm, melody, and harmony, created an “uncomfortable” listening experience that evoked fear and tension. This wasn’t accidental - it was symbolic. The unsettling music reinforced the idea of something dangerous, alien, and out of control.

Rhythm: Breaking the Rules

Rhythms were deliberately dissonant, with accents falling on the weaker beats of the measure. This deviation from expected rhythmic patterns made the music feel unstable and unpredictable, mirroring the film’s stereotyped portrayal of “wild” behavior.

Melody: The sinister Whole-Tone Scale

Melodic lines often used the whole-tone scale, which has no tonal center and incorporates the infamous tritone- an interval historically nicknamed “the devil’s interval.” This choice gave the melody a spinster, ungrounded quality, perfect for conjuring fear. The counterpoint of the piece also incorporates parallel and contrary motion.

Harmony: Augmented Chords

Harmonic progressions relied on the whole-tone scale, often with augmented chords moving in parallel motion. This combination felt jarring and unnatural, as monsters are commonly depicted, amplifying the sense of dissonance.

Phrasing: Odd and Disjointed

Even the structure of the music was unsettling. Weird elisions and phrases in odd numbers disrupted the listener’s expectations, further contributing to the music’s unnerving quality.

Orchestration: Exoticism Amplified

Instrument choices played a huge role in creating the “wild” aesthetic. The xylophone evoked exoticism, hinting at bones (Saint-Sens used the xylophone to depict the dinosaur bones in his “Carnival of Animals”) or African instruments like the marimba. Heavy percussion - bass drum, cymbals, and timpani - mimicked what Western audiences might associate with “native drumming.” These orchestrational choices reinforced harmful, exoticized images of non-Western cultures.

The scenes it could have accompanied

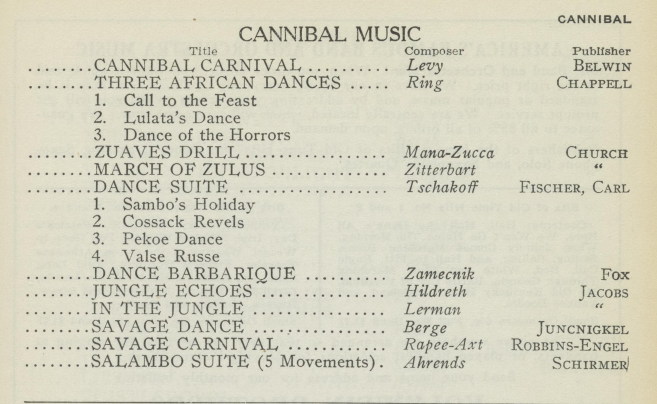

Erno Rapee, in his Encyclopedia of Music for Pictures (1927) categorized themes like “Savage Carnival” under “Cannibals.” That’s a loaded choice, isn’t it? It tells us that film composers of the time were encouraged to use music to portray non-Western cultures as wild, uncivilized, and threatening.

Detail from Erno Rapee’s Encyclopædia of Music for Pictures, New York, 1925

So, why does monster music resonate so strongly with us, even centuries later? It all comes down to the way these eerie sounds tap into our innate responses to the unusual and unsettling. Composers across history have used the building blocks of musical discomfort - clashing notes, strange rhythms, and unpredictable instrumentations - to create soundscapes that perfectly mirror the chaos and unease of the monsters they represent. From Jacques of Liege’s comparisons of note shapes to the Hydra to mythical beasts of Ugolino of Orvieto’s chilling “Chimera scales,” the connection between music and monstrosity has deep historical roots. These unsettling techniques didn’t just appear out of nowhere - because the music depicted monsters it allowed the composers to actively rebel against the norms of pleasing composition, making them perfect for evoking the unnatural and grotesque. Even later, in masque music ant theatrical works, these musical “monsters” continued to evolve. Robert Johnson’s “Come Away, Hecate!” for Thomas Middleton’s The Witch stands out as an example of how disjunct melodies and dissonant rhythms could embody the eerie presence of witches. The unnatural quality of the music turned it into a character in its own right, amplifying the otherworldly atmosphere. These techniques still influence modern horror scores and monster themes. Think of the screeching violins in Psycho - the lineage is unmistakable. Whether it’s medieval Hydra notes or contemporary cinematic soundtracks, the goal remains the same: to disturb, unsettle, and above all, captivate.

Conclusion

In the early 20th century, composers and artists alike leaned heavily on romanticized and often wildly inaccurate depictions of indigenous cultures. One of the most pervasive and damaging stereotypes was the idea of the “jungle cannibal” - a trope that painted entire civilizations as primitive, dangerous, and fundamentally “other.” Ironically, many composers who perpetuated these ideas through their works had no direct contact with the indigenous cultures they portrayed. For instance, the Māori people of New Zeeland - a highly sophisticated and rich civilization - were lumped into the same reductive stereotypes as other indigenous groups as can be seen from Rapee’s generalization in categorizing cannibals with music composed to depict indigenous African cultures. Despite their highly developed traditions, oral histories, and artistry, composers of this era often defaulted to exoticizing them as “wild” or “untamed,” perpetuating the false notion that they lived in jungles and practiced cannibalism. This naturally carries over to the Māori. Our example of the composition “Wild Man’s Dance” is a fine example of this.

This misconception didn’t emerge in a vacuum. At the time, Western societies were steeped in sensationalized accounts from explorers, like Cook, who often exaggerated their stories to make them more thrilling for readers back home. Cannibalism, in particular, became a cultural shorthand for “savagery,” and jungle settings were the default backdrop for these imagined tales. As a result, many Western composers, without ever encountering a Māori person or setting foot in a Polynesian village, simply relied on the narrative that all indigenous people lived in jungles - and those jungles, in turn were populated by cannibals. The oversimplification went even further. “Jungle” became synonymous with the idea of indigenous life in the Western imagination. Never mind the fact that the Māori did not live in jungles at all, but on lush islands with distinct climates and landscapes. The stereotype persisted because it offered a convenient, through lazy, framework: jungle equals primitive, and primitive equals cannibal.

This reductive view had a profound impact on how indigenous peoples were seen and how they were represented in art, music and literature. Entire cultures were dismissed or generalized under the guise of creating “exotic” and “primitive” art, reinforcing deeply ingrained colonial attitudes. The idea that cannibals lived in the jungle wasn’t just a factual error; it was a deliberate narrative tool used to paint indigenous peoples as less than civilized and justify colonial expansion into their lands. These prejudiced views persist today through practices like the “tomahawk chop” and the use of mascots that caricature indigenous peoples, perpetuating harmful stereotypes under the guise of tradition and entertainment. This underscores the need to critically evaluate how artistic works of the past have shaped our understanding of the world. While we may appreciate the beauty of compositions from this era, we should also acknowledge the biases that informed them - and work to challenge the harmful generalizations they perpetuated.

Detail of title page

Monsters, as conceptualized through Jeffery Jerome Cohen’s Monster Theory, serve as cultural mirrors, reflecting the fears, biases, and prejudices of the societies that create the. These creatures embody the anxieties of their time, becoming vessels through which a culture can explore its shadowed corners - those aspects of itself that are repressed, misunderstood, or feared, through art, these monstrous figures offer a form of catharsis for these societies, allowing them to grapple with their own fears and prejudices in a controlled, symbolic manner. The “jungle cannibal,” for example, is not just a reflection of colonial anxiety about the “unknown,” but also fears in art - be it music, literature, or visual storytelling - cultures have historically found a way to process their internal conflicts, even if in doing so, they perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Understanding monsters through this dual lens of cultural reflection and artistic catharsis reveals how deeply intertwined our fears and our creative expressions are, inviting us to examine not only the monsters but the societies that conjured them.

In this post-colonial era, the path to healing from the harm caused by these reductive and dehumanizing practices begins with understanding their origins. By critically examining how stereotypes like the “jungle cannibal” emerged, why they persisted, and the damage they caused, we gain the tools to dismantle them. Acknowledging the role of art, media, and cultural narratives in shaping these harmful perceptions is not just an exercise in historical reckoning - it is a necessary step toward reimagining a future rooted in equity and respect. Understanding the beginnings of these biases allows us to take responsibility for controlling their end, ensuring that the wrongs of the past are not perpetuated in the present. Through education, inclusive storytelling, and commitment to honoring the richness of all cultures, we can foster a process of reconciliation that not only addresses past harm but builds a foundation of mutual respect and understanding for generations to come.